Aching legs, kicking the parking lot curb in Deming, New Mexico – if not out of exhaustion & boredom, then to loose the day’s dirt from our cracked boots. Cow shit, mud, wind-burned faces and angry lungs – we carried what might well have been bags of flour on the surface of our jeans and on our feet all afternoon, leaving behind an impressive pile of dust.

We headed out to the fair grounds from our Luna County motor-lodge every day for a solid week back in September 2010, specifically to see what the rodeo was like outside of the professional circuit. And outside of the circuit, out in the badlands – out where people hold the guttering torch of an agrarian lifestyle – things proved to be contrary to any expectation we could’ve had.

Out here, ranchers exchange stories about the season’s rain, and drought is on their minds. A rash of hardship – of broken men and busted operations, sick livestock and parched crops, lost land, failure, sadness, and suicide – permeates their conversation. There’s also the non-sanctioned events of the working-rancher’s rodeo, cowboys (and girls) telling stories to one another and laughing, exchanging advice and promising prayers and support, good luck and good will. The rodeo performance itself is unflinchingly quiet, even anti-climactic to most of the rodeo crowds we know. The livestock here belong to the ranchers themselves, not a stock agency. Nobody is risking harm to self or harm to their animals – they simply can’t afford it – and that kind of risk just isn’t what we see in pro-rodeo.

At PRCA (Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association) events, many competitors certainly do herald from the ranch-lands. No question about that. But there are endorsement deals – Jack Daniels, Coors, Boot Barn, and Stetson, to name only a few. Those are professional athletes competing for professional money, and it’s a spectator sport. Risks are higher, so is the money, and sometimes people get hurt. In the photo pit and up in the crow’s nest are photographers, print journalists, and videographers, all waiting for that perfect ride. And let’s be honest: many of them are waiting for blood, too. The crowd itself is in for excitement, shaking the grandstand with stomping feet.

With working ranchers, events are skill-based with diminished risk, with little chance of personal injury or damage to livestock. It’s a meeting-ground for regional farmers & ranchers interested in land-management, stock-prices, water resources, and futures markets.

It’s a different game entirely.

Unlike pro-rodeo, women are allowed to compete in events other than barrel racing, and some of them can throw a rope with remarkable skill, rivaling the most celebrated male competitors. Ropers and muggers aren’t as daring, and there’s no Jack Daniel’s tent pouring free samples for onlookers.

These aren’t professional athletes. They’re businessmen.

This is a social gathering for ranchers, whose fates are tied together by market price and rain-water, seasonal planning and farm size. These men and women raise livestock and grow produce. They represent an increasingly rare incarnation of the American laborer. The national average of US ranchers and farmers are approaching sixty years of age, with less than two percent of the US population currently dedicated to producing food. It’s no surprise that events like this are becoming increasingly rare. In fact, when I returned to Luna County in 2011, the rodeo event was canceled due to lack of participation. With few competitors, the prize-pot was far too small to justify the expense of attending.

No gold buckles are awarded here. There are no endorsement deals. No radio station promos or truck dealerships. These men and women pay to play, with the possibility of making business contacts and winning some cash. Eliminate half of the incentive, and the rodeo grounds remain woefully empty.

– – –

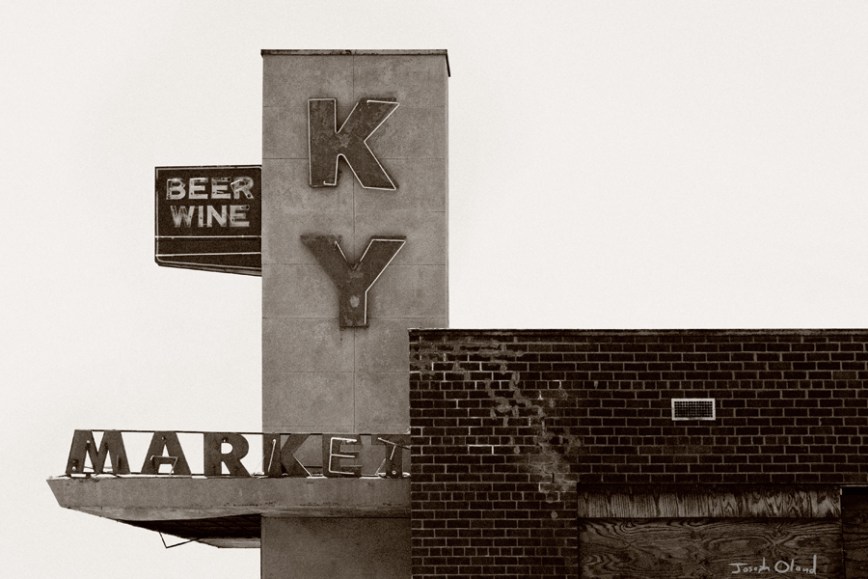

Gray skyscapes and scattered clouds boiling off into the east and a peach mist of dirt in high winds, dissolving as the sun crawls down. We stomp our boots and smoke our cigarettes, leaning against the car, kicking tires and uncapping a bottle of cheap off-brand whiskey in the motel parking lot. The room is dirty but I’m not paying, so there’s no reason to complain. Moldy carpet and four channels, a shitty water-heater that takes twenty minutes just to warm up, and an infuriatingly faulty ice machine – this couldn’t be mistaken for paradise.

But hell – not half bad.

With a case of Mexican beer and a bottle of local wine from local St. Claire, the ‘take’ of the day arrives in wry comments, inside jokes, and several hundred near-useless photographs, choked-out as thoroughly as we were by the dust.

– – –

This is my best memory of Will Seberger – photojournalist, political junky, decent human being. Unafraid to curse in mixed company, he was superhuman in his ability to inject benign conversation with pointed and incendiary commentary – and usually some laughter – and all without coming off as elitist or disrespectful. He passed away unexpectedly in the wee-hours of August 17th, leaving in his wake a constellation of family, friends, fellow journalists, and a wife.

It was this trip to Deming that stands out to me, as both a photographer and a friend. Recently unemployed and living on a buddy’s couch in Tucson, this trip was a gift to me. Will called me up, lord knows why, and asked me along. I didn’t have anything better to do and I felt honored for the invite. This was an opportunity to escape my depression, to get out of the house, to be challenged as a photographer, and to spend time with my friend. I told him I was ‘in’ without skipping a beat.

I’m saddened by how few photographs I actually took of him in the twelve years I knew him. Most of the images presented here, Will was standing right beside me. At the hotel each night, reviewing our work, he didn’t pull punches when critiquing my work. I always appreciated that. It takes a good friend to look you in the eye and say “that’s shit” while loving you at the same time.

– – –

We spent a lot of time outside on the splintered concrete in front of the room, sifting through photos on Will’s laptop, a glowing screen perched on the hood of his JEEP. We smoked a lot of cigarettes outside our non-smoking room, enjoying the autumn weather. Absent a corkscrew, I remember Will cracking the head off a bottle of wine with his survival-knife. He may have ruined that knife, but we enjoyed drink, dag-nabbit.

“Drink up. It’s only ‘day one,’ and we’re only gettin’ dirtier.”

We filled the bathroom sink with ice each afternoon for beer. Twelve hours under the sun each day, rings of mud on the damp bandannas we wrapped over our mouths, local food and cheap Mexican beer were our only comfort outside of conversation. But we talked a lot. And that was nice.

We never complained. This was fun for us.

As the week wore on, the titled presented itself: Apocalypse Cow. We’d wandered into foreign land and buried ourselves in the job. After heat-stroke, booze, and a gaggle of interesting characters – a drunken beast insisting that he was black ops and handed us a copy of his self-authored bio-pic screenplay, a wild-eyed fifty-something donning kilt and ‘zombie apocalypse’ baseball cap telling stories of chemical baths, government medical experiments, anthrax, and cancer – the title seemed appropriate.

“Apocalypse Cow” became the name of the trip. We decided it’d be the name of the gallery show if we ever had one. Sadly, such a show never materialized. We did gather a lot of pictures, though, and we met a lot of great people. I’m confident some of Will’s images wound up in the portfolio, and I know there are a small handful of images that I’m proud of, too. We took notes, collected phone numbers, made plans to return. I just wish we’d found the time to get back out there.

– – –

Our political climate – of vitriol and anger, polarized constituencies and ineffectual representatives – doesn’t have much place out where Will and I ventured. In a saloon, two photographers from the Midwest found each other and struck up a friendship. Our paths were circuitous, but Will and I possessed a healthy blend of old-world values and new-world education. Neither of us were particularly seduced by partisanship. When we worked together, we’d often arrive at the media tent side-by-side. He’s bang on the door and announce: “the liberal media has arrived!”

Always a joke, and always laughter from the other side of the door.

I can’t recall Will ever scoffing at someone’s vote – even if it was against his own horse. He was a man of moral and social integrity, and always fought for what he thought was right. He understood that there are few Truths, and he burned few bridges. He was deeply principled and unforgivably opinionated, but never without a sense of humor to blunt the angst.

Time spent in the borderlands, Will appreciated that some old-world values still exist. He believed that working people matter. Beyond politics and exit polls, network & cable news, party affiliations, gender, or personal bias, he believed in our collective ability to push forward. He found common ground with each and every person he befriended, each and every person he photographed, each an every person he reported on (for the most part). He believed in the possibility of disparate players, approaching the table.

Will was my friend. And I write with a heavy heart that I can’t imagine life being as valuable without him. May he be at peace, and may he and I meet again, against all odds, in the great beyond.

It was a good ride, Will.

If I live to be twice as old and achieve half as much, I’ll be happy.

Thank you. For everything.

-joe