MERCHANDISE AND ORIGINAL CANVAS AVAILABLE HERE

MERCHANDISE AND ORIGINAL CANVAS AVAILABLE HERE

FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE

– – –

When a show reaches a seventh, an eighth, a ninth season, we often begin to notice some changes in the pacing of the story and in the quality of the writing. Truth be told, it’s usually around the fifth season that things start to smell a little funny. This is typically because the show creator, the writers’ room, and the show runners may not, at the very beginning, expected the show to have lasted for so long; the stories become more outlandish and improbable, themes start to repeat themselves, and what may have once been an incendiary and addictive plot begins to wear thin.

This has happened countless times before. When a show proves to be a consistent draw for audiences and ad revenue is consistently high, a show like Dexter or Lost will be renewed for additional seasons again and again, kept on life support until audiences grow weary, until viewership declines and the show dies the death of a million weeping pinhole wounds.

One antidote to this kind of ‘viewer fatigue’ has been the revitalization of serialized story-telling and television show anthologies like True Detective, American Horror Story, and Fargo, where each season is itself a self-contained story. A story can’t grow old and tiresome if the story only lasts for one season.

The real question for our purposes today is this: Is The Walking Dead beginning to overstay its welcome?

Almost all signs point to “absolutely not.” There have been some misfires along the way, but The Walking Dead seems to have maintained it’s momentum. The most common complaint, stretching all the way back to season two, is about the so-called ‘filler episodes.’ This is a legitimate complaint. The pace of the show slows down, audiences suffer emotionally manipulative cliffhangers, and a tremendous amount of time is spent halting the progress of the story. This has certainly been problematic, but it hasn’t made the story measurably less engaging.

In some regards, these ‘filler-episodes’ have been used to exquisite effect, allowing the writers time to explore the emotional depth and complexity of certain characters. Take, as an example, the season six episode “He’s Not Here,” a flashback episode that reveals Morgan’s journey from the edge of madness and back, after a chance encounter with a lone survivor in the woods. This stand-alone episode, with an extended run time of 62 minutes, was undeniably strong and served to temporarily slow the pace of the show.

One of the main reasons The Walking Dead hasn’t lost its luster is because the story isn’t being improvised season-to-season or episode-to-episode like so many other television shows. Like True Blood and Game of Thrones, The Walking Dead is based on material that existed before plans were ever made to adapt it for television. The narrative connective-tissue is already in place; there is already a tried and true blue-print in place before each episode is scripted and before principle photography begins. In fact, some of the more recent problems with The Walking Dead are directly related to story elements that don’t exist in the graphic novels – like the “heapsters” that live in the landfill. The reason it doesn’t feel like these characters have a place in The Walking Dead is specifically because they didn’t originally exist in the source material.

This is one of the main reasons Fear the Walking Dead has struggled to really get on its feet.

All of that being said, season eight starts things off with a bang, a radical shift from the season seven premier. Where one season ago the group was fragmented, weak, and kneeling in the dirt, we now see unification, strength, and resolve. After the despair at the onset of season seven, this is an interesting way to get things rolling. Shifting back and forth with a bearded Rick in an idyllic suburban home, to Rick standing over the graves of Abraham and Glenn, to Rick delivering a rousing speech before mountain an attack against The Saviors, to Rick with battle-weary red eyes speaking of ‘mercy’ (where the episode gets its title), there is still a pattern of emotional manipulation that most fans will find familiar.

We don’t have a clear idea, with these shifting timelines, precisely what’s going on. We don’t know if ‘old Rick and the cane’ are a fantasy or if they’re a vision of things to come. We don’t know if he’s reflecting on his fallen comrades before the assault on the saviors or reflecting about these events sometime thereafter.

The things this episode does, without digging too deep into the plot, is sets the pace for the ‘All Out War’ narrative from the comic books. It starts things out with a bang, with the unified communities organizing a take-down of Negan and his Saviors. We’re still met with the grinning psychopathic confidence of Negan, and it’s difficult to tell how intense the struggle is going to be. But these are fun questions to ask ourselves – questions that will certainly have people tuning in to see what happens next.

One prediction I do have is that the red-eyed Rick with the glint of light dancing on his face will be seen again in the season finale. I believe that this is the moment when the battle with The Saviors is won. When Rick whispers “my mercy prevails over my wrath,” I am confident that the mercy he speaks of will be a mercy he bestows upon Negan. This episode went to great lengths to remind us that Rick has promised to kill Negan personally. My prediction is that Rick won’t kill Negan – that Negan will find a new home in the cinder-block jail Morgan began building back in season six.

Mark my words, reader. Let’s see if I’m right.

READ LAST SEASON’S FINALE REVIEW

– – –

SIGN UP FOR THE LENSEBENDER NEWSLETTER

– – –

– – –

FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE

FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE

FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE

Season two already explains why Ehrmantraut has a grudge against the Salamanca cartel – Hector Salamanca had a civilian “not in the game” killed in the wake of Mike’s truck robbery – and this episode finally illustrates how Ehrmantraut and Gus Fring finally come together. The recipe is simple and as old as time:

Season two already explains why Ehrmantraut has a grudge against the Salamanca cartel – Hector Salamanca had a civilian “not in the game” killed in the wake of Mike’s truck robbery – and this episode finally illustrates how Ehrmantraut and Gus Fring finally come together. The recipe is simple and as old as time:

FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE

FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE It appears that audiences can look forward to seeing how Mike (Jonathan Banks) becomes one of Fring’s chief enforcers. As Mike gets ever-closer to discovering precisely who Fring is, Jonathan Banks continues to deliver a show-stealing performance. The Saul story-line dissolves when we cut to Mike, and audiences try to figure out what he’s thinking, what he’s planning.

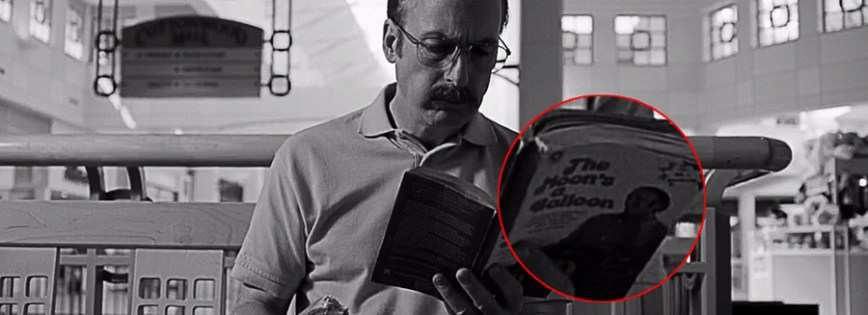

It appears that audiences can look forward to seeing how Mike (Jonathan Banks) becomes one of Fring’s chief enforcers. As Mike gets ever-closer to discovering precisely who Fring is, Jonathan Banks continues to deliver a show-stealing performance. The Saul story-line dissolves when we cut to Mike, and audiences try to figure out what he’s thinking, what he’s planning. “The Moon’s A Balloon” is one of the best-selling memoirs of all time, of a man that contemporary audiences would scarcely recall: David Niven. The book is an account of his life in Hollywood during the 1950’s and 1960’s, beginning with the early loss of his aristocratic father. Stories of service during the second world war follow, and then tales of partying with legends of the silver screen. It’s a gossipy tome, at times earnest and heart-felt, but mostly boastful, about life among the stars while living in Los Angeles.

“The Moon’s A Balloon” is one of the best-selling memoirs of all time, of a man that contemporary audiences would scarcely recall: David Niven. The book is an account of his life in Hollywood during the 1950’s and 1960’s, beginning with the early loss of his aristocratic father. Stories of service during the second world war follow, and then tales of partying with legends of the silver screen. It’s a gossipy tome, at times earnest and heart-felt, but mostly boastful, about life among the stars while living in Los Angeles.