FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE

FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE

– – –

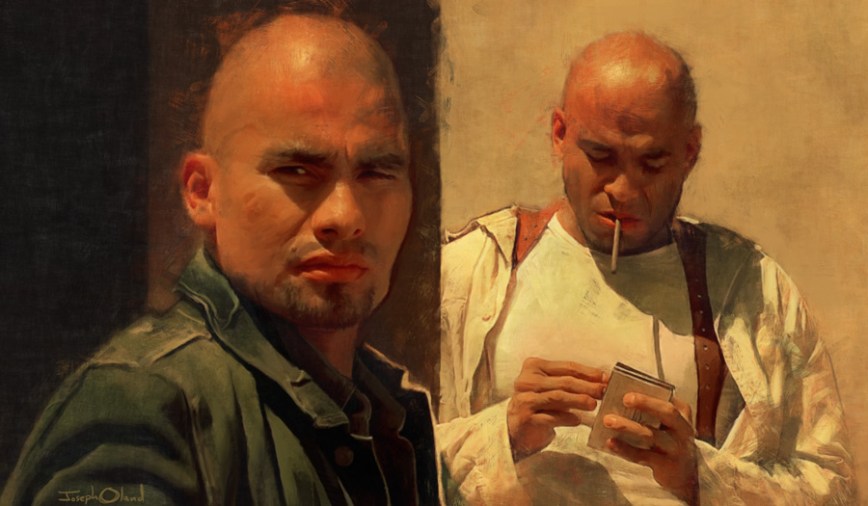

ALL ‘SAUL’ & ‘BREAKING BAD’ MERCHANDISE HERE

One of the greatest assets of Better Call Saul is its treatment of time. The entire series is a framework-piece, beginning in a black-and-white sequence that takes place in the present. This divorces the narrative of Better Call Saul from its Breaking Bad roots. Then we rewind and dive into the prequel narrative, where we learn about Jimmy McGill’s apotheosis. He’s is a fallen god in the present but a serf struggling to feed himself in the beginning of his story.

It may just be possible for Better Call Saul to be both a prequel and a sequel to Breaking Bad. If audiences remain engaged and the show continues, we may just see the present-day narrative extend into the future. It’s a clever slight-of-hand that the writers are playing, and I don’t believe there’s any precedent for this kind of story-telling in television.

Like the previous two episodes of this season – and some moments from the previous two seasons – much of this episode’s story is told in montage, rather than spoken dialogue. This is a curious story-telling trick that motivates audiences to pay attention to the television and not their smart phones, to remain engaged, to empathize with the characters and guess at what they’re thinking, theorize what they’re going to do next. Just as the entire show is a framework piece, this episode functions the same way on a smaller scale, opening with the dangling red sneakers on the power lines south of the border. This opening scene foreshadows the Mike Ehrmantraut (Jonathan Banks) story-line, but we later realize that the scene takes place after the main events of the episode.

*The composition of the frame in the first scene even manages to conveniently crop out the toe of the shoe.

Season two already explains why Ehrmantraut has a grudge against the Salamanca cartel – Hector Salamanca had a civilian “not in the game” killed in the wake of Mike’s truck robbery – and this episode finally illustrates how Ehrmantraut and Gus Fring finally come together. The recipe is simple and as old as time:

Season two already explains why Ehrmantraut has a grudge against the Salamanca cartel – Hector Salamanca had a civilian “not in the game” killed in the wake of Mike’s truck robbery – and this episode finally illustrates how Ehrmantraut and Gus Fring finally come together. The recipe is simple and as old as time:

“The enemy of my enemy is my friend.”

The opposing narrative is more procedural and less intriguing, but we know that it’s building to something. We pick up where we left off last week, with Jimmy (Bob Odenkirk) preparing to deal with the consequences of breaking into his brother’s house and destroying the recording of his confession. Chuck (Michael McKean) has clearly assembled increasingly clever plans to dismantle Jimmy’s career throughout the course of the series, and his recent trickery appears to be the last nail in the coffin – Jimmy isn’t going to forgive him. We already know that Jimmy is going to become a successful (albeit shady) attorney from the Breaking Bad story, so we aren’t overly concerned with the outcome – we’re concerned with how things unfold. All we have to do, as audience members, is wonder how exactly Jimmy is going to get back into the ring and make it happen. Chuck wants Jimmy to give up law, and we already know that it isn’t going to happen, so we wonder.

It’s a new kind of subtle suspense, and it’s a very compelling gimmick.

We all know that Jimmy McGill is a criminal, that he’s conniving and immoral. Somehow, though, we sympathize with him. We watch him struggle professionally, we watch him struggle with his older brother. We somehow want him to succeed, even though we recognize his moral bankruptcy. Television and Hollywood are replete with anti-hero stories, but Better Call Saul has tapped into the story of the anti-hero without dipping into bald-tire cliché. This story is infinitely more human in its exploration of these characters; it is, quite brilliantly, the best adaptation of Goethe’s ‘Faust’ – thematically, not literally – that television has to offer.

READ LAST WEEK’S REVIEW

– – –

SIGN UP FOR THE LENSEBENDER NEWSLETTER

FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE

FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE It appears that audiences can look forward to seeing how Mike (Jonathan Banks) becomes one of Fring’s chief enforcers. As Mike gets ever-closer to discovering precisely who Fring is, Jonathan Banks continues to deliver a show-stealing performance. The Saul story-line dissolves when we cut to Mike, and audiences try to figure out what he’s thinking, what he’s planning.

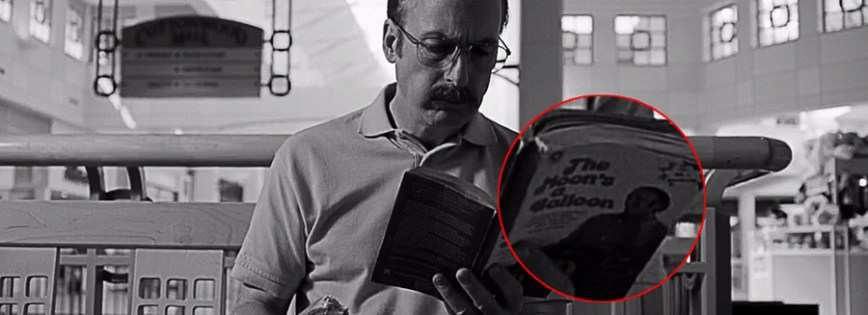

It appears that audiences can look forward to seeing how Mike (Jonathan Banks) becomes one of Fring’s chief enforcers. As Mike gets ever-closer to discovering precisely who Fring is, Jonathan Banks continues to deliver a show-stealing performance. The Saul story-line dissolves when we cut to Mike, and audiences try to figure out what he’s thinking, what he’s planning. “The Moon’s A Balloon” is one of the best-selling memoirs of all time, of a man that contemporary audiences would scarcely recall: David Niven. The book is an account of his life in Hollywood during the 1950’s and 1960’s, beginning with the early loss of his aristocratic father. Stories of service during the second world war follow, and then tales of partying with legends of the silver screen. It’s a gossipy tome, at times earnest and heart-felt, but mostly boastful, about life among the stars while living in Los Angeles.

“The Moon’s A Balloon” is one of the best-selling memoirs of all time, of a man that contemporary audiences would scarcely recall: David Niven. The book is an account of his life in Hollywood during the 1950’s and 1960’s, beginning with the early loss of his aristocratic father. Stories of service during the second world war follow, and then tales of partying with legends of the silver screen. It’s a gossipy tome, at times earnest and heart-felt, but mostly boastful, about life among the stars while living in Los Angeles. FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE

FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE

FINE ART PRINTS AVAILABLE HERE